“Coal”

Song by Tyler Childers

God made coal for the men who sold their lives to West Van Lear

And you keep on digging ’til you get down there

Where it’s darker than your darkest fears

And that woman in the kitchen

She keeps on cookin’, but she ain’t had meat in years

Just live off bread, live off hope, and a pool of a million tears

Now lemme tell you something about the gospel

And make sure that you mark it down

When God spoke out, “Let there be light”

He put the first of us in the ground

And we’ll keep on digging ’til the coming of the Lord Gabriel’s trumpet sounds

‘Cause if you ain’t mining for the company, boy

There ain’t much in this town

We coulda made something of ourselves out there

If we’d listened to the folks that knew

That coal is gonna bury you

Now it’s darker than a dungeon

And it’s deeper than a well

So sometimes, I imagine that I’m getting pretty close to Hell

And in my darkest hour, I cry out to the Lord

He says, “Keep on a-mining, boy, ’cause that’s why you were born”

We coulda made something of ourselves out there

If we’d listened to the folks that knew

That coal is gonna bury you

Listening to those words gives me an odd feeling. There is nothing in them that I can relate to, and yet, in a temporal sense, I am not that far removed from them. At least three of my four grandparents are descendants of coal miners, and I am only two generations away from that song being my life. As I listened to it for the first time in a coffee shop in December 2023, I began to think about my grandfather, Paw Paw (Monford Turner), who died when I was 16. His ancestors were coal miners for as far back as we can trace the line, having left the mines of Great Britain for those of Alabama in the late 1800s. Paw Paw grew up in a mining town in Birmingham called Docena. His father and much of his extended family lived and worked as miners in the town as well. Much of what my grandfather had told me about Docena was through the lyrics of another song: “Sixteen Tons” by Tennessee Ernie Ford.

You load sixteen tons, what do you get?

Another day older and deeper in debt

Saint Peter don’t you call me, ’cause I can’t go

I owe my soul to the company store

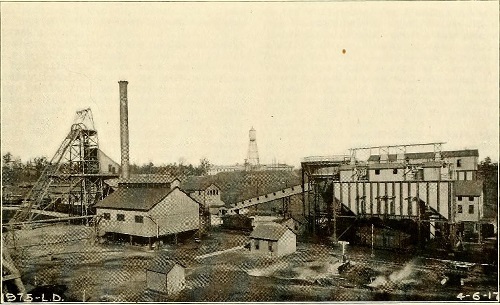

Docena was a company town owned and operated by Tennessee Coal and Iron (TCI), a subsidiary of U.S. Steel. The company owned the mine, the houses, and everything else in the town. They operated the schools, the churches, and, as the song says, the company store. These mining towns were common in Appalachia, and Docena was one of many in the Birmingham area. My grandmother grew up in Edgewater, a neighboring TCI town about 3 miles from Docena. Birmingham is the only place in the world where iron ore, coal, and limestone (the three ingredients for steel) can all be found, and as a result, it was a hugely important place for the steel industry. It is quite literally what put Birmingham on the map, as the city was not founded until 1871, six years after the end of the Civil War.

Sitting in the coffee shop, I began to scour the internet for information on Docena. I found a few pictures of the old mine and a very short description of the town, but that was it. I looked again a few days later, and this time I stumbled upon something great. Samford University had conducted a series of audio interviews with residents of Docena in the 1970s, and the recordings were all online. The first interview I found was with a woman named Melba Wilbanks Kizzire, who was only one year older than my grandfather and lived just a few houses down the street. Her experience was about as close to my grandfather’s as I could hope to find, and I loved listening to her describe the town and her childhood. I listened to it several times before I realized that there were more interviews than just hers on the site. I scrolled through the list and couldn’t believe the name I found. W.B. Turner – my grandfather’s uncle. Listening to that audio was surreal. I didn’t learn any groundbreaking information from the interview, but hearing a long-dead relative speak was pretty neat. My interest had been piqued.

Melba Wilbanks Kizzire Samford Interview

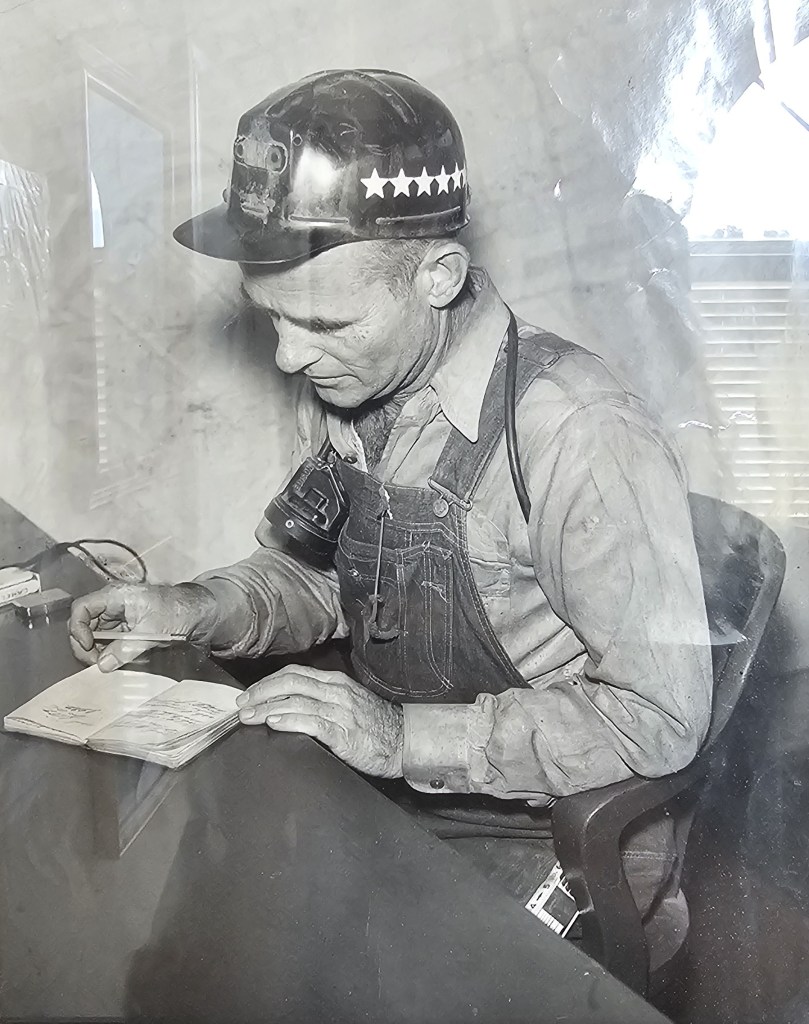

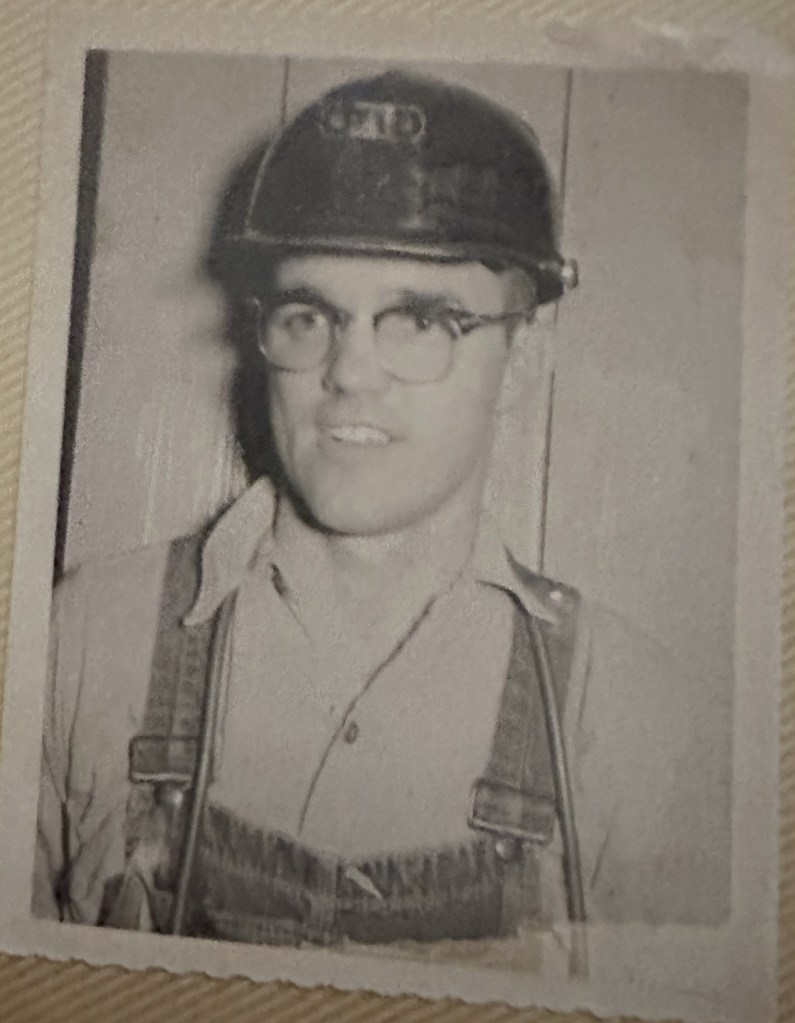

I was incredibly close to my grandfather, and this seemed like a great opportunity to learn more about him and the place he was from. Paw Paw was the 5th of 9 children. Right in the middle. The oldest and youngest siblings were girls, with 7 boys in between. The 11 of them lived in a 3-bedroom house, which they had bought from TCI. Coming from a 2-child household, it’s very difficult for me to imagine what growing up with 8 siblings would be like. Apparently, it was pretty wild, and neighbors would sometimes come to family dinners just to watch the chaos unfold. Paw Paw earned a scholarship through U.S. Steel, graduating from the University of Alabama with a degree in mining engineering in 1963. He went on to work for several mining companies and later worked for the federal government as a mining inspector. He would still have to go into the mines, but he had escaped the life of back-breaking labor that came with being a coal miner. Paw Paw would have preferred not to have anything to do with the mines at all, but U.S. Steel would only pay for his school if he studied mining engineering, and that was the only way he could go to college. Many decades later, when my dad went to college, Paw Paw told him he could major in anything he wanted—except mining engineering.

A few months before Pawpaw died, his oldest brother Clyde came to visit him. I had always enjoyed talking to Clyde, so I drove over to my grandparents’ house to see him. I sat at their kitchen table and just listened to him and my grandfather talk the whole time. He was only there for about an hour, but listening to their conversation had a massive impact on me. Most of it revolved around the two of them debating which of them was going to die first. I have always been comfortable talking about death, but seeing two people at the end of their lives so relaxed about it was remarkable. Looking back on it, I probably should have given them at least a few minutes on their own, but at 16, the thought never occurred to me. Paw Paw had been in a kind of haze for the months leading up to this conversation due to his cancer treatments, but for that hour that he was with Clyde, there was life in his eyes, and he was almost back to normal. I never saw him like that again, and he died several months later. Part of the reason that day was so special for me is that it was the last time I felt like I was really with my grandfather. Clyde and their other brother, Bill, were both at the funeral, and I assumed it would be the last time I would see either of them. I was wrong.

Despite believing he could die any day, Clyde lived another decade. And so did Bill. Pretty remarkable considering they were the second and third oldest of the nine Turner children. When Paw Paw died, they were the only two that remained, and all these years later, that was still the case. While researching Docena, I reached out to both of them and organized for the two of them to meet me, my dad, and my grandmother in Birmingham. However, a few days before we were supposed to leave, Clyde had some health issues, and we decided to reschedule. I was pretty set on seeing them, so I decided to drive down to see Bill on my own. Bill lives just outside of Montgomery, so I drove through Docena and Edgewater on my way down. Both of my grandparents’ childhood homes are gone, but some things from that time are still there. That whole region has been in an economic depression since U.S. Steel greatly reduced its operations and closed the mines in the area. Both towns, particularly Edgewater, were damaged by the massive tornado that went through Birmingham in 2011. Many of the houses that were destroyed or damaged in the storm were never repaired or rebuilt, further exacerbating the already rough conditions in the area. I also drove through some of the graveyards nearby where my ancestors, some of whom were born as far back as the 1700s, are buried.

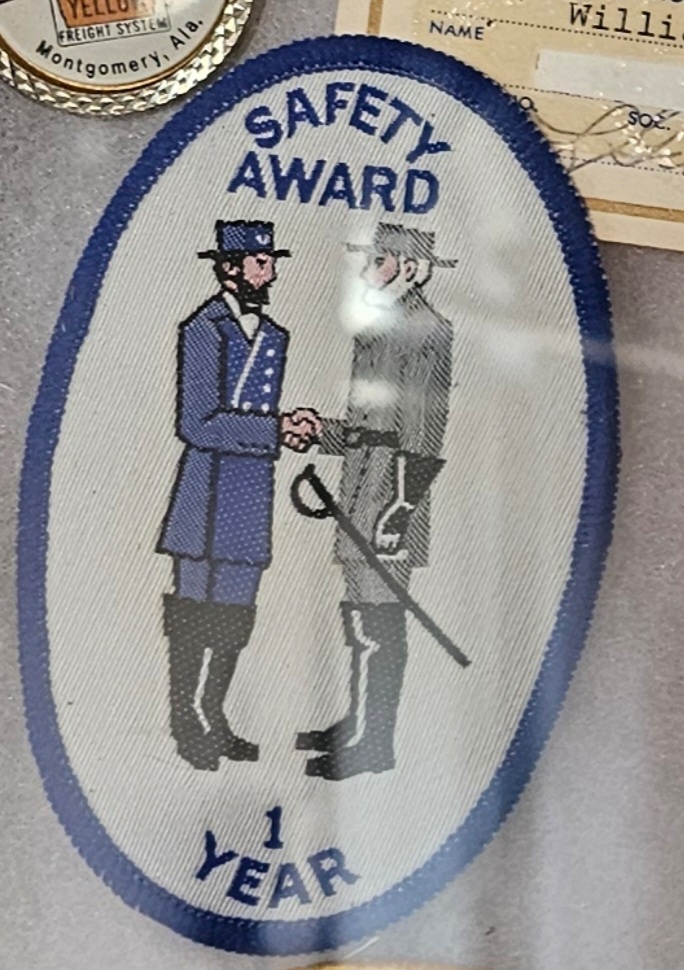

I wasn’t sure what to expect from Bill. The only memory I had of him was watching him load up his car with Paw Paw’s old clothes right after the funeral. My grandmother had given them to him, and I obviously have no problem with him taking them, but in that emotional moment, it rubbed me the wrong way. Paw Paw’s death was very difficult for me, and watching someone take his things away kind of made it all feel real a little too quickly. Thankfully, I got over those feelings immediately. We had a great time together and spent about four hours talking at his kitchen table. I was considering making a documentary about Docena, so I set up my camera and microphone and recorded the whole conversation as an interview. Bill was in incredible shape for an 89-year-old. He was energetic and completely with it. If it weren’t for his poor hearing and eyesight, he could probably live a pretty normal and active life. He reminded me a lot of Paw Paw, which is a good thing. I knew they would have some of the same mannerisms, but I was caught off guard by the little things that they had in common. Bill’s thumbs immediately jumped out to me as the same as Paw Paw’s. I don’t even think I could describe my grandfather’s thumbs, but I noticed them immediately on Bill. But I think it was the differences between the two of them that stood out more. Paw Paw was great. He was almost always in a good mood and smiling… but he was pretty buttoned up. He always did the right thing, always followed all the rules, and he expected you to do the same. Bill was different. He wasn’t doing anything crazy, he was just a little bit looser. I could even see the tail of a tattoo on his bicep, poking out from under his shirt sleeve. I’m not positive I ever even saw Paw Paw wear short sleeves, and he certainly didn’t have any tattoos. Bill didn’t go to college, and he was drafted into the Army just after the end of the Korean War. After a few years in the Army, he spent over 40 years as a truck driver. He proudly showed me the certificate he received upon retiring for having driven over 3 million miles accident-free. That’s over 120x the circumference of the Earth in case you were wondering. He provided me with a lot of great insight into my grandfather and Docena. He was also very close to his father and shared many things with me about him that I had never heard before. It was a great day, and it exceeded my expectations in every way.

A few weeks later, we finally went down to see Clyde. He had just moved into a veterans’ home and was still getting adjusted. We walked into his room and were greeted by Fox News playing at full volume. That would be the first genetic link to my grandfather I would notice that day. Once we got the TV turned down, we all sat down and caught up. Clyde was also remarkably cogent for someone his age (92). However, unlike Bill, it was clear that he was in a good bit of pain. He sat in a motorized wheelchair and spent some time going over his medical problems, all of which sounded pretty miserable. My dad and grandmother left us alone, and Clyde and I talked for about 90 minutes. I once again recorded the conversation, but part of me wishes I hadn’t. Bill was incredibly comfortable with the camera and seemed to forget it was there immediately. Clyde never forgot it was there. He was a little more guarded and even made some comments directly to the camera. This hesitancy towards being recorded was probably wise, and I can definitely relate to it; however, I do feel that it somewhat hindered the conversation. Unlike Bill, Clyde had worked in the mine at Docena for a brief time. I was eager to hear about his experiences, and I have linked that part of the interview below. After the interview, he asked me if I wanted to have lunch with him, and I said yes. I thought he meant in the cafeteria at the facility, but he meant at a restaurant, so I got my car and drove it around to the entrance of the veteran’s home. Clyde was already waiting at the curb for me, which is when I realized that I couldn’t fit his wheelchair in my car. I got out to tell him, but he had already pushed himself up and out of the chair. I helped him into the car, and we left, with his wheelchair just sitting at the curb outside. We had a nice lunch, and I feel like he was much more relaxed without me recording what he was saying. I hadn’t thought about it until we got to the restaurant, but probably over half of the time I had spent with my grandfather had been at family dinners or out to eat at restaurants. Because of this, almost everything Clyde did while we were at the restaurant reminded me of Paw Paw.

Going down to see them again was incredibly fulfilling, but I was a little disappointed I wasn’t able to see them together. A little over a year later, I began feeling the urge to go see them again. So I did. Last month, I drove down to Bill’s house and spent the night with him. The next morning, we loaded up the car and set forth for Trussville to see Clyde. Clyde had told us the night before that he had a doctor’s appointment scheduled in the morning and would call us when he was finished. As Bill and I were approaching Trussville, we had yet to hear from him. We were both starting to worry that it wasn’t going to work out yet again, but we decided to kill some time to keep our hopes alive. I checked my phone and found a Bucee’s just a few miles out of the way. I asked Bill if he had ever been to one, and he said no, so I nonchalantly began the navigation on my phone. Having spent four decades as a truck driver, Bill knows the roads pretty well. He immediately realized that I was not going in the right direction to get to Clyde’s house. He began shuffling uncomfortably in his seat and looking out the window. I could tell what was happening, but I didn’t want to say anything. After a few minutes, he finally asked me what road we were on. I told him I didn’t know, and he told me we were going the wrong way. I said that we were low on gas and that I had started navigation on my phone to a gas station. He didn’t seem to like this answer, but he just said okay and continued looking out the window nervously. A few minutes later, we arrived at that beavery oasis. Once I told him where we were going, he became very excited. I pumped our gas and then led him through the crowded store. He seemed to be completely blown away, and he even saved the Bucee’s wrapper from his BBQ sandwich, so I think he really enjoyed the experience. I have often said that I think Paw Paw would be a huge fan of Bucee’s, so it was cool to see his brother experience it for the first time.

After eating my lunch slowly and stalling as much as possible, we still hadn’t heard from Clyde. It was looking like we weren’t going to be able to see him, but we decided to drive by his house just to make sure he wasn’t home. When we pulled into his driveway, the garage doors were closed, and it looked like no one was there. Bill’s wife, Josephine, had given us a pound cake to give to Clyde and his wife, Mary. Both of us were very disappointed we weren’t going to be able to see him, but we decided to leave the pound cake at the door and head out. Just as I got out of the car and began to walk to the front door, the garage door opened, and Mary walked outside. Clyde had left his phone at home, but they had just returned from the doctor’s office. We were both ecstatic and quickly made our way inside the house.

We spent the next hour and a half talking in Clyde’s room. I was fascinated by what I saw. Bill and Clyde were a combined 183 years old, and yet, anyone on the planet would have been able to identify who the big brother was. Clyde dominated the room and the conversation, and everyone else fell in line. His doctor had just told him to stop taking almost all of his medication, and he proudly lined up all the pill bottles that he was excited to throw away on the table. He then tried to give it all to Bill and me. We both declined at first, but after he insisted we take some, Bill took home a few bottles of pills, and I went home with a box of Narcan. Learning from my experience when I was 16, I decided to leave the room to give the brothers a few minutes to talk on their own. However, almost immediately after I stepped out of the room, Mary came and joined the conversation, so I went back in. I was thrilled to be able to get the brothers back together for what might be the final time. It was only 11 days before the 10th anniversary of Paw Paw’s death, so it felt like a bit of a tribute to him as well. As Bill and I were pulling out of Clyde’s driveway, I told him that this was the third time I thought I was seeing Clyde for the last time. He had proven me wrong the last two, so I said we’d see if he could do it again.

This time, I was right. Clyde died this Sunday at the age of 93, just 45 days after we saw him. I am incredibly grateful to have spent some time with him before his death, and I’m really glad that I started on this research journey while he was still alive. Bill is all that remains of the Turner siblings now. At 90, I’d say he has a decent chance of beating Clyde’s record, and I hope he is able to. I went back and watched my interview with Clyde this week, which feels much more valuable now that he is gone. I only wish that I had done something similar with my grandfather before he died. Clyde had 22 great-grandchildren, and Bill has 5 great-great-grandchildren, so there is no shortage of Turners. Hopefully, the work I have done can help some of them learn about where they came from.